Article

|

5 mins

|

February 11, 2026

Metabolic health describes how efficiently the body converts food into energy and maintains normal levels of blood sugar, blood pressure, cholesterol, and body fat. “Metabolically healthy” is a state when these parameters remain within normal ranges without long-term medication.

Metabolic problems usually develop gradually. When abdominal fat increases and blood sugar, cholesterol, and blood pressure rise together, the risk of diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and liver disease increases significantly. Clinically, this clustering of abnormalities is referred to as metabolic syndrome.

Understanding metabolism, its working and disruption, helps explain the impact of lifestyle factors – diet, physical activity, sleep, and stress, in long-term health.

The Condition: What Is Metabolic Health?

Metabolic health reflects the integrated regulation of energy balance by multiple organs and hormonal systems. In clinical practice, it is assessed through the presence or absence of metabolic syndrome.

Metabolic syndrome is diagnosed when three or more of the following are present:

Increased waist circumference (abdominal obesity)

Elevated fasting blood glucose

High Triglycerides

Low HDL (“good”) cholesterol

Elevated blood pressure

From this perspective, metabolic health is reflected in the absence of metabolic syndrome, indicating effective regulation of glucose, lipids, blood pressure, and body fat distribution without pharmacological support.

Physiology of Metabolic Health

2.1 Normal Regulation

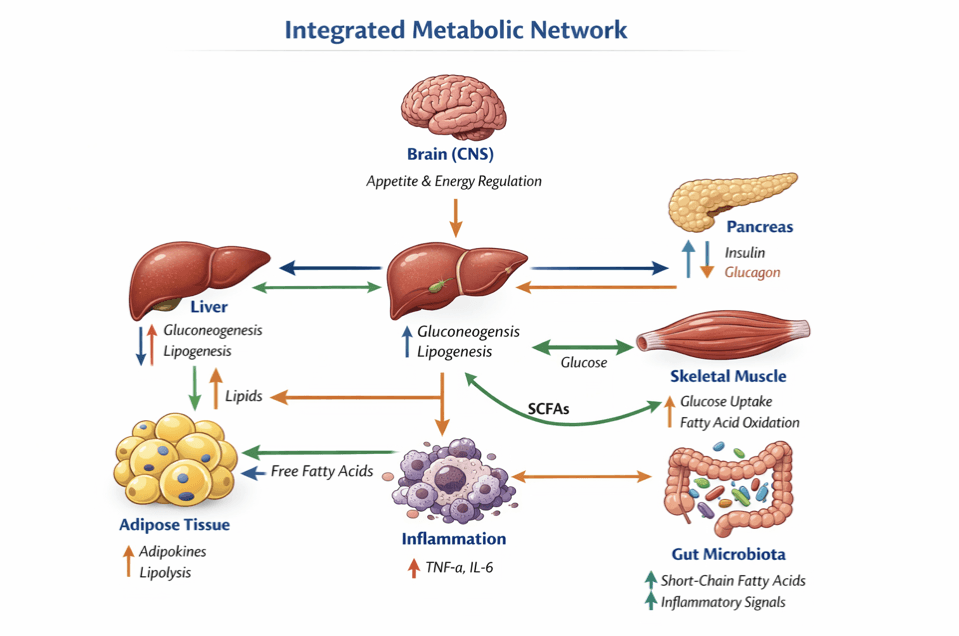

Metabolic health depends on the body’s ability to respond appropriately to feeding, fasting, physical activity, and rest. This regulation is achieved through coordinated communication between the pancreas, liver, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, central nervous system, and the gut.

2.2 Hormonal Control

Following food intake, rising blood glucose stimulates insulin release from the pancreas. Insulin promotes glucose uptake by skeletal muscle (primary site for blood glucose clearance), suppresses glucose production in the liver, and supports energy storage in adipose tissue. During fasting, glucagon maintains blood glucose by stimulating hepatic glucose output.

Adipose tissue releases hormones such as leptin and adiponectin, which influence appetite, insulin sensitivity, and lipid metabolism. Gut-derived hormones, including GLP-1, modulate insulin secretion and satiety. This integrated hormonal signal(s) regulate energy balance.

2.3 Organ-Level Integration

Skeletal muscle is the primary site of glucose disposal and a key determinant of insulin sensitivity.

The liver regulates glucose and lipid availability by switching between storage and production.

Adipose tissue (also known as body fat) stores excess energy and acts as an endocrine organ.

The gut microbiome contributes to nutrient processing, inflammatory regulation, and metabolic signaling.

Working synchronously, the body maintains metabolic flexibility, allowing efficient adaption to changing energy demands.

Figure 1. Integrated Metabolic Network (Schematic Description)

Depicts the interaction between the pancreas, liver, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, central nervous system, and gut microbiota in regulating metabolic health. Insulin and glucagon control glucose exchange between liver, muscle, and adipose tissue. Adipokines such as leptin and adiponectin signal energy status and influence insulin sensitivity, while gut hormones such as GLP-1 regulate appetite and post-meal glucose control. Inflammatory mediators arising from dysfunctional adipose tissue impair insulin signaling. Bidirectional arrows indicate continuous feedback and coordination required to maintain metabolic balance.

Pathophysiology: Development of Metabolic Dysfunction

Metabolic dysfunction develops when the coordinated regulatory pathways illustrated in Figure 1 is persistently disrupted - Chronic excess caloric intake, physical inactivity, sleep disturbance, and prolonged psychosocial stress act together to overwhelm adaptive metabolic mechanisms, resulting in progressive metabolic inflexibility.

3.1 Insulin Resistance

A central feature of metabolic dysfunction is insulin resistance, characterised by a reduced cellular response to insulin in skeletal muscle, liver, and adipose tissue. Excess lipid accumulation within hepatocytes and myocytes promotes lipotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, and activation of inflammatory and cellular stress pathways. These processes impair insulin signalling, leading to reduced glucose uptake, increased hepatic glucose production, and compensatory hyperinsulinaemia. Sustained β-cell stress ultimately increases the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

3.2 Adipose Tissue Dysfunction and Inflammation

As adipose tissue expands beyond its physiological storage capacity, it undergoes structural and functional changes. Adipocyte hypertrophy is accompanied by immune cell infiltration and increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This inflammatory state disrupts adipokine signalling, reduces insulin sensitivity, and contributes to endothelial dysfunction, positioning adipose tissue as a central driver—not merely a consequence—of metabolic disease.

3.3 Dyslipidaemia and Multiorgan Effects

Impaired lipid handling leads to elevated triglycerides, reduced HDL cholesterol, and increased atherogenic lipoproteins. These changes accelerate atherosclerosis and increase cardiovascular risk. Simultaneously, excess lipid deposition and metabolic stress affect the liver, kidneys, and central nervous system, reinforcing the systemic nature of metabolic dysfunction.

3.4 Systemic Consequences

Metabolic disturbances occur concurrently across multiple organs with metabolic disease manifesting as a systemic disorder with wide-ranging effects:

Liver: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and progression to fibrosis

Cardiovascular system: hypertension and atherosclerosis

Kidneys: increased risk of chronic kidney disease

Brain: associations with cognitive decline and neurodegenerative risk

Preventive Bio signals Generated by the Body

The body continuously generates physiological signals that reflect metabolic state and function. These biosignals, when monitored longitudinally, provide early indicators of metabolic dysfunction before clinical disease manifests. Advances in sensor technology have enabled the continuous capture of these signals in free-living conditions, shifting metabolic health assessment from intermittent clinical snapshots to dynamic, personalised monitoring.

4.1 Glucose Fluctuations

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems measure interstitial glucose concentrations throughout the day and night, revealing high-resolution glycemic dynamics that are not captured by single-point measurements such as fasting glucose or HbA1c. CGM-derived metrics include postprandial glucose peaks, glycemic variability, time spent in hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia, and glucose curve shapes. These patterns have been used to identify metabolic subphenotypes associated with muscle insulin resistance, β-cell dysfunction, and impaired incretin action. Glucose fluctuation patterns also enable the detection of early dysglycemia in individuals with normal fasting glucose, supporting preventive intervention before progression to prediabetes or diabetes.

4.2 Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability

Heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) reflect autonomic nervous system regulation, which is closely linked to metabolic health. Reduced HRV is associated with insulin resistance, obesity, and metabolic syndrome. Wearable devices equipped with photoplethysmography (PPG) sensors continuously capture HR and HRV in ambulatory settings. Integration of HR and HRV data with physical activity and glucose monitoring improves the prediction of individual glucose dynamics and metabolic responses. HRV patterns have also been explored as predictive signals for hypoglycemia risk, enabling real-time warning systems.

4.3 Physical Activity and Step Patterns

Accelerometry-based sensors embedded in wearable devices quantify physical activity intensity, duration, and timing. Step count, sedentary time, and circadian stability of activity patterns are digital markers of cardiometabolic health. Cross-sectional studies have demonstrated associations between activity tracker-derived metrics and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, body mass index, and waist circumference in working-age adults. Activity data also improve the accuracy of personalized glucose prediction models by capturing the metabolic effects of exercise and movement.

4.4 Sleep and Circadian Rhythms

Sleep duration, quality, and timing are critical determinants of metabolic health. Wearable sensors derive sleep metrics from heart rate, movement, and skin temperature data. Disrupted sleep and circadian misalignment are associated with increased risk of metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. Recent studies have shown that circadian biomarkers derived from wearable data, including sleep–wake timing and circadian energy distribution, predict metabolic risk and individual glucose responses to meals. These findings position sleep and circadian rhythm monitoring as modifiable preventive targets.

4.5 Skin Temperature and Electrodermal Activity

Peripheral skin temperature and electrodermal activity (EDA), measured via wrist-worn sensors, reflect autonomic and thermoregulatory processes influenced by metabolic state. Multimodal models incorporating skin temperature, EDA, heart rate, and accelerometry have been used to estimate HbA1c and CGM-derived glycemic variability metrics in proof-of-concept studies, achieving high accuracy in small validation cohorts. These signals also capture stress responses and circadian rhythms, both of which influence metabolic regulation.

4.6 Blood Pressure and Respiratory Rate

Although less extensively validated in the current digital biomarker literature, continuous or frequent blood pressure monitoring and respiratory rate tracking represent emerging biosignals for metabolic health assessment.

Digital Biomarkers (Dbx) for Recording and Understanding Biosignals

Digital biomarkers are objective; quantifiable physiological and behavioral data collected through digital health technologies. These biomarkers transform raw biosignals into clinically meaningful metrics that can be used for screening, diagnosis, monitoring, and personalized intervention in metabolic health.

Wearable sensor patterns, analyzed with explainable machine learning, have been used to develop proof-of-concept hypoglycemia warning systems. These systems detect early physiological signals of impending hypoglycemia, enabling timely intervention.

5.1 Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGM)

CGM devices measure interstitial glucose concentrations continuously via subcutaneous sensors. Modern CGM systems provide real-time glucose readings every 1–5 minutes and are increasingly used beyond diabetes management for metabolic health optimization in non-diabetic populations. CGM data enable the derivation of digital biomarkers such as glucose curve shapes, postprandial area under the curve (AUC), and glycemic variability indices. Large-scale studies have demonstrated that CGM-based digital biomarkers, when integrated with machine learning models, can classify metabolic subphenotypes with high accuracy and support personalized dietary recommendations.

5.2 Smartwatches and Photoplethysmography (PPG) Wristbands

PPG-derived heart rate and HRV, combined with motion data, have been used to predict interstitial glucose deviations. These devices also measure sleep, activity, and circadian patterns, enabling comprehensive metabolic phenotyping. The widespread adoption of smartwatches positions them as scalable platforms for population-level metabolic health monitoring.

5.3 Multi-Sensor Patches and Research Wearables

Emerging wearable patches integrate multiple sensors (skin temperature, EDA, PPG, accelerometry) into a single device for comprehensive biosignal capture. These devices are being evaluated in research settings for remote metabolic monitoring and risk prediction. Prototype systems using multi-sensor data and machine learning models have demonstrated feasibility for continuous metabolic health assessment, though clinical validation and regulatory approval remain ongoing.

Analytical Approaches and Machine Learning

The transformation of biosignals into actionable digital biomarkers relies on advanced analytical methods, including machine learning, dynamical modeling, and explainable artificial intelligence.

6.1 Feature Engineering and Explainable Machine Learning

Machine learning models combine glucose traces, activity logs, sleep data, meal timing, and other biosignals to predict postprandial glucose responses, next day glycemia, and metabolic risk. Explainable AI techniques provide interpretable insights into which factors (e.g., meal composition, exercise timing, sleep quality) drive individual metabolic responses, enabling personalized behavioral recommendations.

6.2 Bayesian Dynamical and Mechanistic Models

Bayesian modeling frameworks learn individual circadian baselines and quantify how food intake, physical activity, and sleep perturb glucose dynamics. These models improve personalized glucose prediction and support the identification of optimal intervention timing.

6.3 Ensemble and Tree-Based Machine Learning

Gradient-boosted decision trees (e.g., LightGBM) and ensemble methods have been applied to predict interstitial glucose from non-invasive wearable sensor data, achieving root mean square errors (RMSE) of approximately 18.5 mg/dL and mean absolute percentage errors (MAPE) of 15.6% in controlled cohorts.

6.4 Early Detection of Metabolic Dysfunction

Multimodal biosignal integration enables the identification of early metabolic subphenotypes and dysglycemia in individuals without overt disease. CGM-derived glucose curve shapes, combined with machine learning, have classified metabolic subphenotypes (muscle insulin resistance, β-cell deficiency, impaired incretin action) with AUCs up to 95% in discovery cohorts and 84–88% in at-home validation studies. Proof-of-concept studies have also demonstrated the feasibility of classifying normoglycemia versus prediabetes using CGM and smartwatch data with high sensitivity and precision.

Predictive, Preventive and Personalized intervention

Digital biomarkers support just-in-time behavioral feedback and personalized intervention. Models predicting meal timing and postprandial glucose peaks enable real-time recommendations to avoid glycemic excursions. Large-scale digital health programs integrating CGM, wearables, and machine learning have reported significant reductions in hyperglycemia, glucose variability, hypoglycemia, and body weight, demonstrating translational prevention potential.

The Next Frontier

Growing epidemic of obesity and fatty liver disease now demands a shift from episodic testing to Dbxenabled, Predictive, Preventive, and Personalized intervention that continuously senses risk and dynamically adapts care.

At a deeper physiological level, digital biomarkers generated by CGM, skin patches, wearables with PPG sensors, combined with explainable machine learning, support just-in-time coaching, personalized nutrition, and dynamic tailoring of activity and sleep patterns, turning the same bio signals that once passively reflected disease into active levers for its prevention. Given the high prevalence of Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease, MASLD, and the tight coupling of fatty liver with visceral adiposity, dysglycemia, and circadian disruption, positioning Dbx as the next generation of bio signals is not speculative; it is a cohortbacked pathway to Predictive (early subphenotyping), Preventive (realtime lifestyle correction), and Personalized (individual responseguided) management of metabolic and liver disease at population scale.

References

Alberti, K. G. M. M., Eckel, R. H., Grundy, S. M., Zimmet, P. Z., Cleeman, J. I., Donato, K. A., Fruchart, J.-C., James, W. P. T., Loria, C. M., & Smith, S. C. (2009). Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. The Lancet, 373(9679), 1640–1645. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61794-3

Bent, B., Cho, P. J., Henriquez, M., Wittmann, A., Thacker, C., Mogi, M., Feinglos, M., & Crowley, M. J. (2021). Engineering digital biomarkers of interstitial glucose from noninvasive smartwatches. npj Digital Medicine, 4, Article 89. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41746-021-00465-W

Bent, B., Cho, P. J., Wittmann, A. H., Thacker, C., Muppidi, S., Feinglos, M. N., & Crowley, M. J. (2021). Non-invasive wearables for remote monitoring of HbA1c and glucose variability: proof of concept. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care, 9(1), Article e002027. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJDRC-2020-002027

DeFronzo, R. A., Ferrannini, E., Groop, L., Henry, R. R., Herman, W. H., Holst, J. J., & Weiss, R. (2015). Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 1, Article 15019. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.19

Dehghani Zahedani, A., Veluvali, A., McLaughlin, T., & Agarwal, P. (2023). Digital health application integrating wearable data and behavioral patterns improves metabolic health. npj Digital Medicine, 6, Article 216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-023-00956-y

Hotamisligil, G. S. (2006). Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature, 444(7121), 860–867. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05485

Kim, J.-K., Mun, S., & Lee, S.-W. (2024). Detection and analysis of circadian biomarkers for metabolic syndrome using wearable data and explainable artificial intelligence. JMIR Preprints. https://doi.org/10.2196/preprints.69328

Ling, C., & Rönn, T. (2024). Epigenetics in human metabolic disease. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 12(2), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(23)00285-4

Maritsch, M., Föll, S., Lehmann, V., Bérubé, C., Kraus, M., Feuerriegel, S., Kowatsch, T., Züger, T., Stettler, C., Fleisch, E., & Wortmann, F. (2020). Towards wearable-based hypoglycemia detection and warning in diabetes. In Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–8). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3334480.3382808

Metwally, A. A., Perelman, D., Park, H., Aghaeepour, N.,

Zhou, W., Shalaeva, D., Ratliff, W., Chaix, A., Dunn, J., & Snyder, M. P. (2024). Prediction of metabolic subphenotypes of type 2 diabetes via continuous glucose monitoring and machine learning. Nature Biomedical Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-024-01311-6

Phillips, N. E., Collet, T.-H., & Naef, F. (2023). Uncovering personalized glucose responses and circadian rhythms from multiple wearable biosensors with Bayesian dynamical modeling. Cell Reports Methods, 3(7), Article 100545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crmeth.2023.100545

Rykov, Y., Thach, T.-Q., Dunleavy, G., Roberts, A. C., Christopoulos, G., Soh, C.-K., Car, J., & Dinh-Le, C. (2020). Activity tracker-based metrics as digital markers of cardiometabolic health in working adults: Cross-sectional study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(1), Article e16409. https://doi.org/10.2196/16409

Saklayen, M. G. (2024). The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. The Lancet, 403(10430), 1425–1436. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00312-5

Tatli, D., Papapanagiotou, V., Liakos, A., Kotsa, K., & Delopoulos, A. (2024). Prediabetes detection in unconstrained conditions using wearable sensors. Clinical Nutrition Open Science, 57, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutos.2024.09.013

van den Brink, W., van den Broek, T. J., Palmisano, S., Sire, J., Sluik, D., Feskens, E. J. M., & de Graaf, C. (2022). Digital biomarkers for personalized nutrition: Predicting meal moments and interstitial glucose with non-invasive, wearable technologies. Nutrients, 14(21), Article 4465. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214465

Varghese, T., Schultz, J., & Patel, S. (2023). Wearable and digital devices to monitor and treat metabolic diseases. Nature Metabolism, 5(4), 563–571. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-023-00778-y

Get in touch:

ORANGEHUE LIFE SCIENCES PVT LTD

63/2, Kodichikkanahalli Main Rd, Bommanahalli,

Bengaluru, 560 068 , India

© 2026 OHUE / All Rights Reserved